By way of background, Sir Konrad has had an immensely successful career, serving as a judge in both the (UK) Court of Appeal and the European Court of Justice. Born in Berlin in the 1930s, Hitler’s rise and the personal tragedy of becoming orphaned near the end of the 2nd World War played a central part in shaping his remarkable life. Soon after the heart-breaking death of his parents he was brought to England as a small boy by his uncle. He was subsequently educated in Birmingham, and did his National Service as a commissioned officer in the Lancashire Fusiliers. He later studied law at Pembroke College Cambridge and went on to become a barrister, then Queen’s Counsel and later High Court and Appeal Court Judge before taking on his role in Europe.

[On a lighter note, of interest to many of our members, Sir Konrad is also a member of a local choir!]

Trained to a degree as a historian and influenced by his own history, Sir Konrad has found himself in recent times interested in slogans about ‘Taking back control [of finances, borders and laws]’. With this in mind, his talk to us was philosophical rather than political. His surmise is that, in reality, states can seldom have full ‘control’.

Firstly, Sir Konrad pointed out that ‘no state can shut itself off from others’. For example, states influence one another’s finances. The pound, for instance, has devalued several times as a result of changing behaviours by other countries towards the purchase of British goods. Nations can therefore never really be ‘in control of their money’.

Generally, each state also wants something that is incompatible with what another state wants. Sir Konrad gave the analogy of a family where the children’s differing desires are sometimes also incompatible. For instance, little Robert might always want chocolate cake for dessert, while Mary wants fruit salad. Families resolve this by allowing Robert to have his cake today on the understanding that he puts up with Mary having salad tomorrow. Similarly, states can’t always have what they want and need to persuade each other that there are ‘deals to be done’. As for the family, one party may benefit at one point in time, the other at another point. Such give-and-take, Sir Konrad feels, is the framework for democracy.

Going back in time to how the concept of sovereignty arose, Sir Konrad spoke about the numerous small states that existed just after the reformation, with Protestants and Catholics persecuting one another. A ‘rule of areas’ scheme developed where states decided who would be what; they then left each other alone. Each state thus had sovereign power within its borders. But such sovereignty has its weak point. What if, as in Germany, a state decides to persecute a certain group (in Germany’s case, Jews)? Must all the other states stand by and let the slaughter continue so as not to interfere with a country’s sovereignty?

This eventually gave rise to the notion of ‘human rights’, with states permitted to ‘interfere’ if other states threaten the rights of certain groups. This all needs balances and checks to guide when ‘interference’ should occur, which, in effect, is what is decided in Strasbourg in the European Court of Human Rights.

There is also a place for the pooling of sovereignty. For example, in NATO each member state formally undertakes to go to the aid of another if it is invaded. The deterrent value is important. Invading states may first ask themselves: ‘Is it worth attacking this bear that has so many paws?’ Such considerations construct a safer world, where ‘the selfishness of the strong doesn’t result in misery of the weak’. Of course this is not easily done, and a strong nation may yet trample on another country elsewhere.

In summary, Sir Konrad suggested that there can be no real ‘control’ over finances, borders or laws for states and that sovereignty has its place – but as an intellectual concept, a function and not a goal. And despite being surrounded by water (unlike other European nations), the UK can still be dramatically affected by external factors.

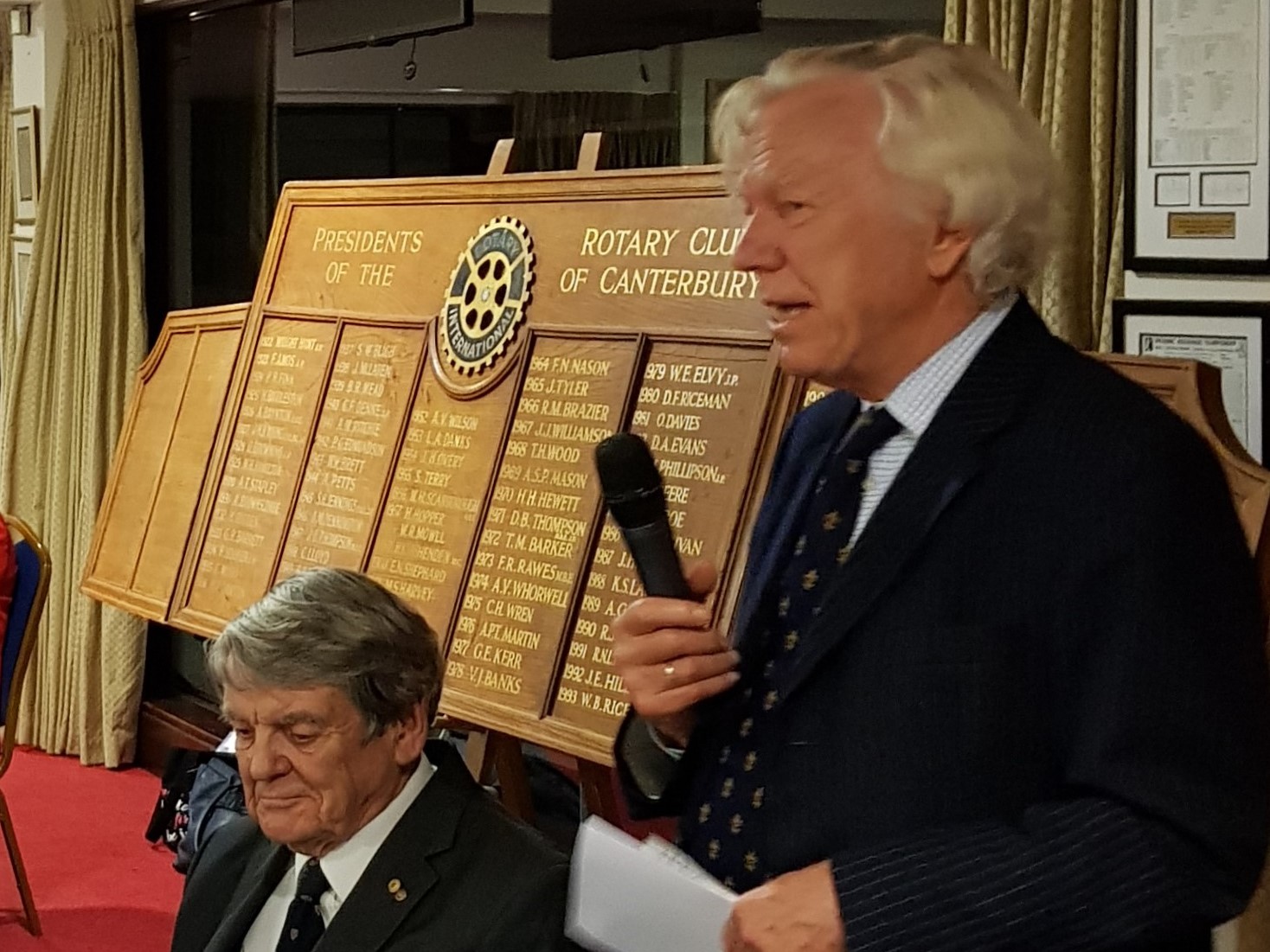

Picture: Sir Konrad gives his talk to Rotarians.