Erika spoke to our Members & their guests yesterday evening by Zoom, all the way from Edinburgh. She was introduced to us by our President Stephen Thompson.

Erika is a Digital Education Designer and Teacher at The University of Edinburgh and works on the development of online courses on International Climate Solutions. She has a longstanding interest in climate change and carbon footprints and her current work focuses on climate change in Malawi. For our talk, however, Erika focussed on climate change and the UK.

First off, Erika reminded us of the difference between the terms “weather” and “climate” – people often mix these up. The main difference, we learnt, is time. “Weather” refers to conditions over a short period of time, while “climate” refers to how the atmosphere behaves over a relatively long period of time, or the “average” weather for a defined region during a specific period (usually 30 years). Thus, the UK is said to have a “maritime temperate climate”, although its weather can include occasional snowfall or a heatwave.

Next, we learnt about three things that affect our global climate.

The first is heat. There are two heat sources for Earth: heat from the Earth’s core (which is pretty constant) and “incoming” heat from the Sun. While the heat given out by the Sun is also pretty constant, the amount that reaches us is governed by the Earth’s changing orbit, how far away our planet is from the Sun and the angle at which the sunlight hits our atmosphere. This orbit means that there’s a slow cycle in the amount of heat our planet receives from the Sun (called a Milankovitch cycle).

The second major thing affecting our climate is called “Albedo” – the Earth’s reflectivity. This is affected by the Earth’s surface: darker parts of the planet absorb more heat than whiter areas (e.g. snow-covered areas). Thus, changes to the Earth’s surface affect Albedo.

Third – greenhouses gases. While we’ve all heard about these gases, Erika reminded us that they trap heat, keeping the Earth warm. Without such gases “oceans would turn to ice,” said Erika – so in that sense such gases are a good thing! (But an increase in such gases is not – something Erika covered later.)

It turns out that the Earth’s climate actually fluctuates naturally and gradually over a course of millennia. An interesting chart showed us temperature trends over a span of 420,000 years. There are major, periodic peaks and troughs. These big climate changes have been quite destructive when they occurred. For instance, around 125,000 years ago high temperatures and droughts led to Homo Sapiens migrating from Africa to other continents. In the last “cool” phase on Earth, Neanderthal man became extinct (40,000 years ago)!

It seems that during the last 10,000 years (a tiny portion to the right of the chart), we have been in a warm part of the cycle that was slowly cooling (with periodic smaller peaks and troughs of warming and cooling).

So, one might ask, if there are natural cycles why should we be worried now?

Well, it seems that in the last 200 years, that cooling that we would expect to see in a natural system has reversed, and the rate of warming that we are experiencing now has been faster than ever before. “It’s this rate of change that is of concern,” said Erika, adding “it puts us and other species in danger”. And this level of warming cannot be explained by natural forces alone – something Erika illustrated with a further chart. Basically, while temperatures over the last 200 years simulated on the basis of natural activity were fairly level, in reality the observed temperatures have been increasing quite dramatically. Clearly, human activity accounts for this. “The media may imply otherwise,” said Erika, “but the science is actually very settled on this point.”

The culprit is excess greenhouse gas emissions – the by-product of manmade activity. Agriculture/farming, electricity/heat production, transportation and industry are the some of the major producers of man-made greenhouse gases.

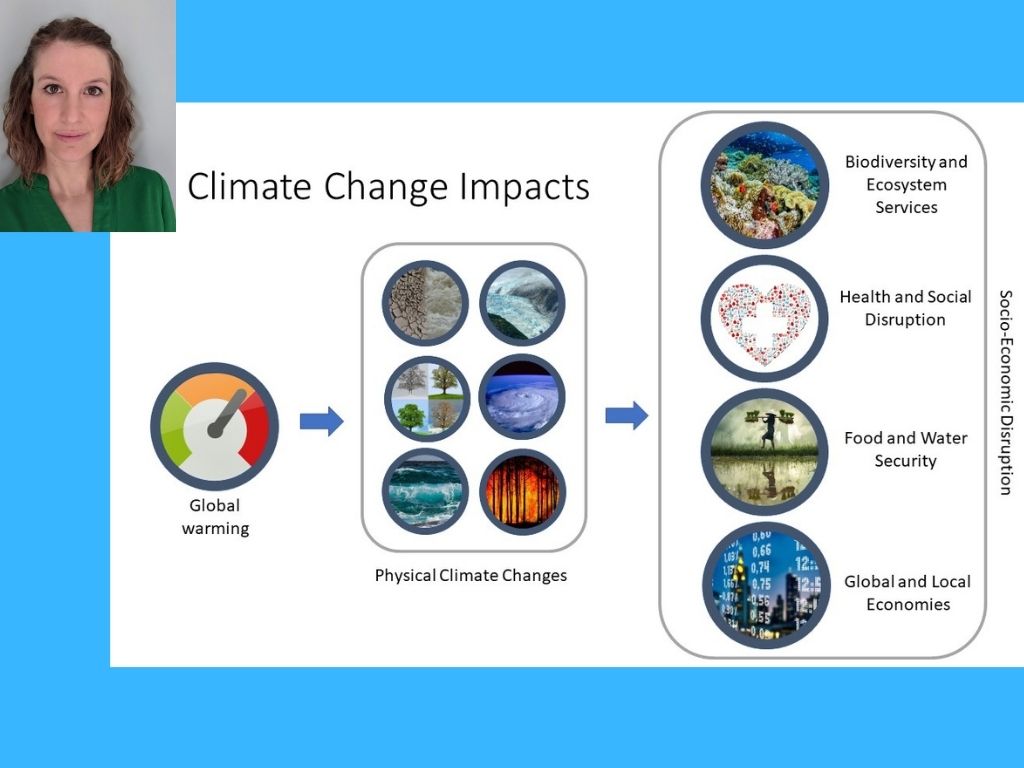

Erika went on to talk about impacts of climate change. “An extra couple of degrees might sound quite nice on a cold December evening like today,” said Erika, but “the impacts of a degree or two of change in in the climate are actually pretty massive and worrying.”

Erika illustrated this in a couple of startling slides. The 1.2°C of global warming that we have already experienced since pre-industrial times has already affected precipitation (rain), the timing of seasons, sea levels and ocean pH, storm patterns and intense fires. In turn, these have had, and will continue to have, a huge impact on biodiversity & ecosystems, our health and society, our food and water security, and global and local economies.

With increased temperatures, for example, we’re more likely to get extreme events that affect animal and insect migration, their pollination, and thereby biodiversity and agriculture. We are, we heard, experiencing a “6th period of mass extinction”. For example, if we keep warming at the current rates, 99% of corals are likely to be gone by the middle of the century.

Effects of climate change on human health could be direct (e.g. storms or fires) or indirect (affecting water supplies and so impacting on disease). Droughts, for example, can lead to food shortages that then lead to conflict and violence. (Giving Syria as an example, Erika pointed out that during 2007-2010, 85% of livestock in Eastern Syria died and the country experienced debilitating crop failures. This resulted in poverty and unemployment, and those affected become more vulnerable to exploitation by extremist groups.) There is also an effect on global and local economies. By 2050, climate change could lead to an annual reduction of 23 trillion dollars to the global economy; relatively, this is more than the effects of Covid-19 had on the economy in 2020.

“We do have options,” said Erika. We learnt that in 2015 the World agreed to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Our challenge now is to limit our emissions. “So far this is not happening at the global level at a big enough scale. At current levels of commitment, it is doubtful we will limit warming to 2°C, least of all 1.5 degrees! Without ramping up global emission targets, the World will suffer more impacts,” said Erika.

Erika also showed us how global warming is not distributed evenly around the planet, with some countries or regions affected much more than others. She also pointed out that different regions of the world have different levels of resistance/resilience, and that those least responsible for greenhouse gases emissions are most likely to be hit hardest by their impacts.

For the rest of her talk Erika largely focused on the UK and climate change impacts here in the South East. She showed us a chart with bars in blue and red showing temperature fluctuations since 1884, clearly demonstrating that temperatures have been rising over the last few decades. Worryingly, all of the UK’s record-breaking hottest years have occurred since 2002.

Apparently, the South East has had more increases than the rest of the country. Higher temperatures mean higher seas, increased rainfall and increased heatwaves. UK’s summers are likely to get hotter and drier, while winters will have more rain and storms. The largest changes, again, are likely in the South East. Two dramatic graphs showed best- and worst-case scenarios.

“Kent has high vulnerability,” said Erika, showing newspaper pictures of recent floods and storms and pictures of affected bird and butterfly species to illustrate the signs of climate change that we might have noticed locally. “Small businesses may struggle to adapt,” said Erika. Agriculture will be impacted and there will be more pests, water shortages etc. The quality and quantity of food grown in the UK, and the food which we import, will likely change.

Focusing on these agricultural shifts, Erika reminded us that though the agricultural sector in the UK is relatively small, it manages around 25% of UK’s land and employs around 1/2 million people.

While there may be some benefits to having a warmer climate – new crops such as grapes and peaches, a longer growing season and an earlier spring – climate change will have considerable concomitant negative impacts. A longer growing season would affect soil fertility and water supply, for example. Temperatures that are too high will decrease the quality of crops and increase the survival of pests such as aphids and the Colorado beetle (already threatening potato crops here). High temperatures give dangerous conditions for farmworkers and livestock. Increased temperatures could affect milk yields and animal reproduction. It could also lead to death. “By the 2nd half of the century we will need to keep cattle indoors for much longer periods due to the risk of heat stress,” said Erika.

We also learnt that 1/4 of Kent’s land is less than 5 metres above sea level. Therefore, storm surges would give increased likelihood of flooding. Aside from the direct effects of floods, the rising waters would wash away nutrients from the soil, and salt water could damage the soil long-term for further agriculture.

All of these issues have already started to happen, and more issues will be seen in the 2030s, 40s and 50s – “so this is NOT a far-off problem, as we might think,” emphasised Erika – “action is needed now!”

The agricultural industry is major contributor to climate change: “Our global food system accounts for 1/4 of all greenhouse gas emissions. Without action to reduce agri-related emissions, we will not be able to meet our climate change targets” was Erika’s stark warning, before she added: “There’s a need to work with farmers, food producers and retailers to increase climate resilience”.

Erika ended her riveting talk by highlighting that “all consumers need to look at their food use – and reduce red meat intake and food waste, for example. They also need to vote for policies that will support farmers, allowing them to adapt to future climate changes and to make production more climate-friendly.”

There were several interesting questions for Erika at the end before Stephen gave his thanks and everyone gave Erika a warm round of applause.

Picture: One of Erika’s slides on climate change impacts. (Inset: Picture of Erika.) Picture credits: Erika Warnatzsch.