Hayley is the project manager for Bird Wise North Kent, which is part of a partnership that helps to “raise awareness of protected birds that spend time on our coastline every year”. The North Kent arm (serving Gravesend to Whitstable) was set up in 2017 to address concerns about the disturbance to birds across the North Kent marshes. (A separate arm exists for East Kent – Whitstable to Pegwell Bay).

The partnership consists of a number of organisations – including Canterbury City Council, Kent County Council, Swale Borough Council, the Kent Wildlife Trust, the Kent Developers Group, the RSPB and others. Its work is funded by contributions from developers that have any development projects within 6 km of the local coast. The aim of the North Kent arm is to lessen impact of development to birdlife in the North Kent marshes.

When thinking of the impact of new developments on birds, most of us might only think of physical issues such as impingement on natural habitats. But in fact, any sort of development means more humans – and with that, more disturbance.

Hayley divided her talk into two parts – in the first she told us about the work of Bird Wise, and in the second she focussed on local coastal birds.

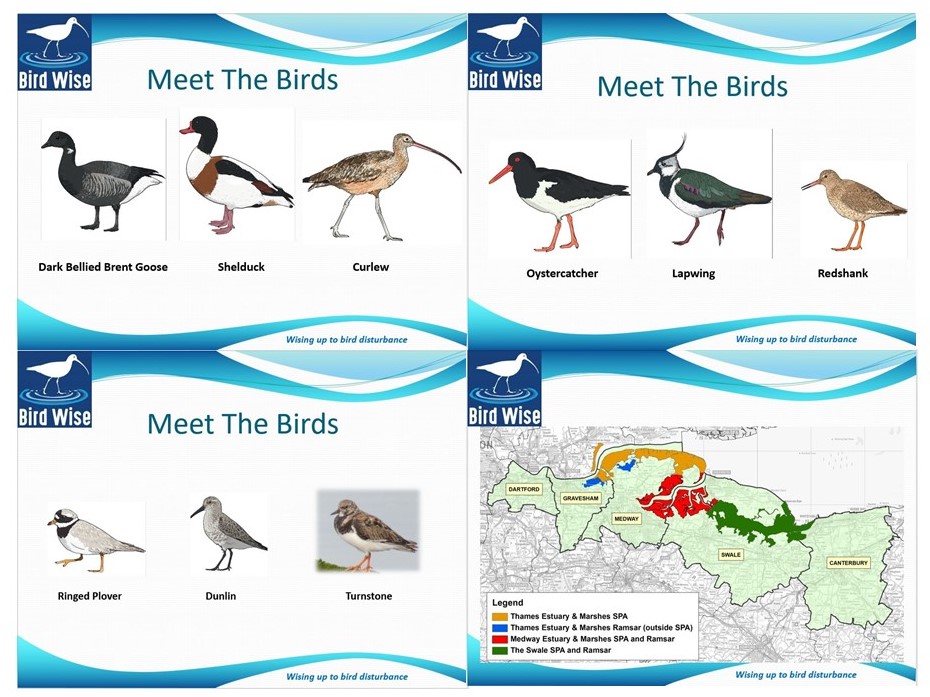

Hayley showed us a map of North Kent Bird Wise’s area – spanning all the way from Dartford through Gravesham, Medway and Swale to Canterbury (around 17,000 hectares providing vital habitat – see map). This includes the Thames Estuary special protection area (SPA), the Medway Estuary SPA and the Swale SPA.

Hayley told us about the Ramsar Convention (an intergovernmental Convention on Wetlands guiding international cooperation for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources) named after the city of Ramsar in Iran, where the convention was signed back in 1971. The fact that three parts of our local marshes fall under this convention indicates just how important these marshes are deemed to be internationally.

We learnt that around quarter of a million (250,000) birds depend on the North Kent marshes – especially during our winter. It seems that birds come to this area because of its wide range of habitats – e.g. shingle, foreshore and salt marsh. This means that there’s a diverse range of foods for the birds, so a diverse range of birds are attracted to the area. We learnt that birds come here in winter from the Arctic to enjoy “warmer” weather and, for them, longer days. Once here they spend their time feeding and resting and building up energy and strength for their long journeys back.

Bird Wise has seasonal rangers that help its work by speaking to the public and giving advice to them on how to decrease their impact on birdlife. “But, aside from habitat issues, what sort of disturbance do we cause to the birds?”, you might ask. Well, it turns out that we cause all sorts of recreational disturbance – although different birds do have a different tolerance, depending where they have come from. For instance, cyclists, or dogs off leashes, or even us humans wandering off a path, can affect birds. The cyclists and dogs can startle birds that are not used to them. Even a “friendly” dog may be perceived as a threat by a bird, such that it flies away. This uses up vital energy that the bird then needs to replace – after all, it’s building itself up towards returning to where it came from, often thousands of miles away. What this drain on its energy means is that the bird may take the long journey back when it’s in a poor condition…or that it isn’t in the right condition to breed. By not sticking to a footpath we can also scare birds or tread on ground nests. It’s all quite thought provoking: how our simple pleasures can affect wildlife, even though we may think of ourselves as nature lovers.

Ultimately, us humans need to mitigate the effect we have on birdlife by modifying our own behaviours – for instance, by sticking to paths and keeping dogs on leashes; what we see as a dog “playing” with a bird is actually quite stressful for the wild animal.

Bird Wise’s rangers inform the public about this – Hayley says she often takes her own dog with her when out as dog lovers are more receptive to advice from other dog lovers. Currently, signage is used and codes of practice are being developed – “it’s important to note that people aren’t doing anything illegal,” said Hayley, adding that “changes in behaviour take time”.

Bird Wise normally runs a “Coastal Canines Club” which helps dog owners enjoy guided tours without harming birds. These tours had to stop because of Covid but should start again soon. Bird Wise also hope to start all their other normal activities again as lockdown eases – e.g. visiting libraries and having stalls at events.

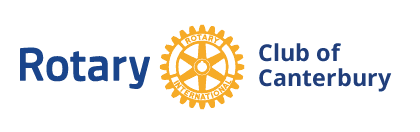

The second part of Hayley’s talk was dedicated to “meeting” the local birds (see picture).

The Dark Bellied Brent Goose, we learnt, flies here from Siberia. Its numbers depend on Lemmings. Why? Because it’s greatest predator, the Arctic Fox, prefers to eat Lemming over the Goose!

The Shelduck, with its distinctive red bill, is our largest duck (though this year there have been sightings of Eider Ducks at Seasalter). The Shelducks nest in rabbit burrows and other holes – and females without chicks serve as “babysitters” while parent birds are out looking for food.

Curlews, easily recognised with their long, downward-turning bills, have a beautiful call. While they normally eat small crustaceans they may move to neighbouring fields when the tide comes in, when they will eat earthworms. Interestingly, males and females have different bill lengths, meaning they dig to different levels for food and therefore don’t compete with each other.

Oystercatchers, it turns out, don’t actually eat a lot of oysters, preferring other easier-to-access shellfish which they get out by using their bill like a hammer or tweezer. These noisy, gregarious creatures are waders and nest on the ground. They are easily scared when brooding; if they fly off, their eggs are exposed to the cold or to gulls, larger raptors and foxes.

Lapwings, with their distinctive crest (males) and iridescent plumage, are nicknamed “Peewits” because of their call. They get the name “Lapwing” from the flapping noise they make as they flap their large wings.

Redshanks are relatively unimpressive looks-wise – but these birds (of which there are few breeding pairs in our area) act as the “sentinel” of the marshes, being the first to raise the alarm if they sense danger. (Even Bird Wise rangers have to take extra care as they can alarm them!)

Ringed plovers nest on shingle, with nests carefully camouflaged and barely visible…and therefore easily disturbed by careless activities. The eggs themselves, like speckled brown stones, also blend in with the surrounding shingle.

The Dunlin, we learnt, are currently all in Scandinavia where they breed.

Lastly, we learnt about Turnstones – so named, no surprise, because of their habit of turning stones to look for food. In parts of East Anglia they are known as “Tangle pickers” because of their habit of picking tangles of seaweed. Also currently in Scandinavia, these birds are clever creatures, “exploiting” local fishermen by stealing their live bait when the fishermen’s backs are turned!

At the end of Hayley’s talk the floor was opened to questions, which ranged from finding out the difference between “twitchers” and “birders” to understanding the traffic light system for levels of endangered bird species. (Egrets and Grey Herons, it seems, are on the “green” list. The former reflects conservation success as, in Edwardian times, the birds were hunted down for the feathers that ladies would wear in their hats; it was this that led to the setting up of the RSPB).

The vote of thanks was led by Rotarian Brian Dobinson and the audience gave an appreciative round of applause.

You can find out more about Bird Wise here.

Follow the North Kent branch on social media @birdwisenk

Picture: Composite image of some of the birds that we learnt about during Hayley’s talk and a map showing the area covered by Bird Wise North Kent. Picture credit: Bird Wise North Kent (reproduced with permission).